On the Shoulders of Giants

After two winters, Project SNOWstorm has accomplished a lot — and we’re getting ready for another winter of work.

So far, this winter has been a lesson in the complexities of Snowy Owl dynamics. There was an early movement of owls into the northern prairies and western Great Lakes, many of which have shown signs of food stress. Notable numbers of those weak owls turned up at rehab centers in Wisconsin and lakeshore locations like Marquette, Michigan. On the East Coast, on the other hand, Norman Smith has encountered mostly healthy, normal-weight young owls at Logan Airport in Boston. What we’ll have learned by the end of the winter of 2015-16 will be another interesting chapter in the Project SNOWstorm story.

While the work that our team of collaborators has been doing feels new and exciting in this age of electronic communication, we are really standing on the shoulders of giants who have worked with Snowy Owls and other raptors for years. This blog is the first in what will be an irregular series about those that have come before us, and to whom we owe a large debt of gratitude for laying the foundation that we are building on.

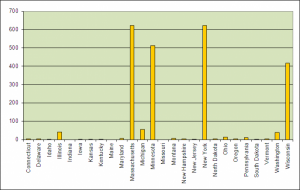

Statewide Snowy Owl banding totals for the period 1960-2014. Data from the U.S.G.S. Bird Banding Laboratory.

Statewide Snowy Owl banding totals for the period 1960-2014. Data from the U.S.G.S. Bird Banding Laboratory.

Those groundbreaking ornithologists and citizen scientists did not have the technology that we possess today, but they used tried-and-true bird banding techniques, and a big dose of creativity, to learn about the winter ways of Snowy Owls. Looking into the Bird Banding Laboratory’s database, it quickly becomes obvious that prior to the irruption of 2013-14, there are four states in the lower 48 that have been the centers of winter Snowy Owl banding. Each of these states has its own history and key researchers whose passion brought us to where we are today.

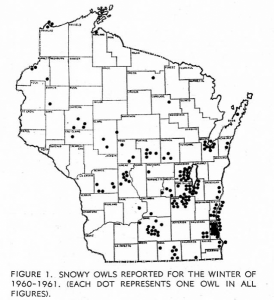

In many ways the story of Snowy Owl winter research (and the antecedents of Project SNOWstorm) begins in my home state of Wisconsin — not in 2013-14, but in 1960-61 when I was only 6 years old and had no idea what a Snowy Owl was. During that winter there was, as in 2013-14, a huge irruption of Snowy Owls into Wisconsin. That inspired Fran Hamerstrom, then president of the Wisconsin Society for Ornithology (WSO), and a group of adventurous raptor banders including Dan Berger, Helmut Muelller and Chuck Sindelar, to conduct “Operation Snowy Owl” (Hamerstrom and Hamerstrom 1960; Hussong 1960).

Distribution of Snowy Owls reported in Wisconsin during the winter of 1960-61. Map courtesy of the Wisconsin Society of Ornithology Passenger Pigeon (see Sindelar 1966).

Together they and their colleagues conducted the first coordinated effort to study the winter irruption and subsequent distribution of Snowy Owls on a regional scale. There were no GPS-GSM transmitters capable of tracking an owl’s movements, so they use spray paint to color-mark the white feathers of the owls they trapped and banded.

Left to right, Fran Hamerstrom, Dan Berger, Cynthia Schachter and Nancy Mueller spray painting a Snowy Owl in a suburban basement. Image courtesy of The Iowa State University Press Ames Iowa, photo taken by Orvell Peterson.

Left to right, Fran Hamerstrom, Dan Berger, Cynthia Schachter and Nancy Mueller spray painting a Snowy Owl in a suburban basement. Image courtesy of The Iowa State University Press Ames Iowa, photo taken by Orvell Peterson.

In the 1960s, information traveled far more slowly than today, relying on post cards, letters, and phone calls. In many respects, Project SNOWstorm is simply a modern-day incarnation of Operation Snowy Owl — one conducted on a much wider scale, using nearly instantaneous methods of communication, cutting-edge tracking technology, and engaging a larger and more widespread set of collaborators.

Birding With a Purpose (1984), image courtesy of The Iowa State University Press, Ames Iowa.

Birding With a Purpose (1984), image courtesy of The Iowa State University Press, Ames Iowa.

Most of the stories that these pioneering Snowy Owl banders have are quickly disappearing as the aging participants pass away. Fortunately, Hamerstrom recorded some of them in her book Birding With a Purpose, in which she devotes three chapters to some of the antics associated with field research in the 1960s. If we’d met any of the participants in Operation Snowy Owl that winter, I suspect many of us would have the same reaction as did one county sheriff, whose conversation with Fran is retold in the book.

The sheriff asks, “How about the man who was in the car with me first?”

“Berger. He’s a good scientist and he runs a laundromat down in the Milwaukee slums,” Hamerstom replies.

“I didn’t want to ask him … Now I see you do it too. Why do you paint your fingernails all those colors?”

“It’s just accidental,” she explained. “We don’t do it on purpose.”

“Accidental?” gasped the sheriff.

“Someone has to hold the owls when we spray paint their feathers. The paint gets on our hands. It washes off skin, but it doesn’t come off fingernails.”

The sheriff then asked if he could become a “gabboon” — Fran’s term for the young apprentices that she and her biologist husband Frederick employed on their many research projects. She was only half-kidding when she granted the officer “probationary” gabboon status.

He may not have realized what he was in for. Among the antics from those early winters, which Fran recalled, were dropping Volkswagon buses through thin ice on lakes in east-central Wisconsin while trapping Snowy Owls for banding — not just once, but multiple times, sometimes with visiting foreign researchers along for the ride.

Fran Hamerstrom releasing a Snowy Owl on the ice of a east central Wisconsin lake during the winter of 1960-61. Image courtesy of the Cedar Grove Ornithological Research Station archives, photo taken by Tom Meiklejohn.

Fran Hamerstrom releasing a Snowy Owl on the ice of a east central Wisconsin lake during the winter of 1960-61. Image courtesy of the Cedar Grove Ornithological Research Station archives, photo taken by Tom Meiklejohn.

Fran Hamerstom was Aldo Leopold’s only female graduate student. She followed Frederick from Boston to the prairies of central Wisconsin to save the Greater Prairie-chicken from extirpation in the Badger State — which they did. In the process the two of them left a rich legacy of wildlife research, not just for the work on “chickens” but also for Fran’s work with Northern Harriers (detailed in her book, Harrier, Hawk of the Marshes) and other raptors. Fran’s Snowy Owl banding work occurred between 1961 and 1974 when she banded a total of 67 owls. Together these two ornithologists trained a long list of successful ornithologists and field workers.

A Snowy Owl caught on the Fond du Lac, Wisconsin dump. The pigeon – after a moment of panic – has resumed eating corn in the trap. Image courtesy of The Iowa State University Press Ames Iowa, photo taken by Tom Meiklejohn.

A Snowy Owl caught on the Fond du Lac, Wisconsin dump. The pigeon – after a moment of panic – has resumed eating corn in the trap. Image courtesy of The Iowa State University Press Ames Iowa, photo taken by Tom Meiklejohn.

The team that conducted Operation Snowy Owl were pioneers in many ways. The trapping methods they developed are still widely used, such as using noose traps known as bal-chatris to capture Snowy Owls, and using nylon stockings or tubes to hold raptors safely during banding. While painting owls may seem crude to us now, it was used very successfully by these intrepid researchers back in the 1960s.

Helmut Mueller (left) and Dan Berger (right) in front of the original Cedar Grove Ornithological Research Station hawk trapping blind in 1950. Image courtesy of the Cedar Grove Ornithological Research Station archives, photo taken remotely by Helmut Mueller.

Helmut Mueller (left) and Dan Berger (right) in front of the original Cedar Grove Ornithological Research Station hawk trapping blind in 1950. Image courtesy of the Cedar Grove Ornithological Research Station archives, photo taken remotely by Helmut Mueller.

Two other important players in Operation Snowy Owl were well-established Wisconsin raptor researchers in their own rights. The Cedar Grove Ornithological Station, along the Lake Michigan shore a short drive north of Milwaukee, had originally been started by ornithologists from the Milwaukee Public Museum in 1935. World War II interrupted research there, but in 1950 Dan Berger and Helmut Mueller revived the effort to count, trap, and band raptors at Cedar Grove. The station has operated every year since (for a history of Cedar Grove, click here).

Over the years this field research station has banded over 43,000 raptors, produced a long list of scientific papers, and trained many young field ornithologists, including introducing Fran Hamerstrom to raptor trapping techniques. And not too surprisingly, they even banded a Snowy Owl at Cedar Grove. Between 1960 and 1993 Dan Berger banded 39 Snowy Owls. Helmut Mueller’s Snowy Owl banding work occurred during 1960-61 when he banded 12 owls. Other ornithologists that were introduced to raptor research through Cedar Grove include Chuck Sindelar, another member of Operation Snowy Owl, and Tom Erdman – Curator of the Richter Museum of Natural History at the University of Wisconsin Green Bay, who would go on to band 41 Snowy Owls in and around Green Bay Wisconsin, as well as mentor both myself and another Project SNOWstorm collaborator, Eugene Jacobs.

Sindelar, an experienced eagle bander, went on to be one of the key individuals in monitoring the recovery of the Bald Eagle in Wisconsin. Between 1966 and 1974 Chuck would band 28 Snowy Owls in Wisconsin and another 19 in Minnesota. Chuck also sponsored and trained a young man who would become an important Snowy Owl bander in the Duluth, MN, area — Dave Evans. Most of the nearly 500 Snowy Owls that have been banded in Minnesota since 1974 are thanks to Evans’ efforts. The Wisconsin total of over 425 owls is largely the result of Operation Snowy Owl and several other banders. There are two other individuals that in combination have banded more Snowy Owls in Wisconsin than any of the others – Don Follen and his associate Kenneth Luepke. Follen banded between 1964 and 1987 and, after Follen passed away, Luepke continued Don’s work through 2003. These two citizen scientists, working west of the Wisconsin River in west central Wisconsin, banded a total of 174 Snowy Owls, just over 40% of the Wisconsin bandings to date.

A record catch of Snowy Owls during the winter of 1960-61 in Wisconsin. From left to right, Errol Schulter, Tanya Schulter, Chuck Sindelar, Fran Hamerstrom, Paul Drake and Alan Jenkins. Image courtesy of The Iowa State University Press Ames Iowa, photo taken by Orvell Peterson.

A record catch of Snowy Owls during the winter of 1960-61 in Wisconsin. From left to right, Errol Schulter, Tanya Schulter, Chuck Sindelar, Fran Hamerstrom, Paul Drake and Alan Jenkins. Image courtesy of The Iowa State University Press Ames Iowa, photo taken by Orvell Peterson.

So, what were the results from Operation Snowy Owl? While documenting 162 Snowy Owl observations across Wisconsin in a single winter was no small accomplishment (Sindelar 1966), in total the team banded 58 Snowy Owls that winter, laying the foundation for those to come.

There’s a direct line from Operation Snowy Owl to Project SNOWstorm. It’s no coincidence that the second Snowy Owl fitted with one of Project SNOWstorm’s GPS-GSM transmitters was trapped by Eugene Jacobs, a central Wisconsin raptor expert who can also trace his roots back through Tom Erdman, Cedar Grove, and the Hamerstorms.

Even more fittingly, the owl that he trapped back in December 2013 was Buena Vista, named for the grasslands in the heart of Wisconsin’s prairie-chicken range, only a few miles from the Hamerstroms’ home.

In the best tradition of Operation Snowy Owl, Project SNOWstorm collaborators will be out and about this winter, continuing our efforts to better understand this charismatic owl. Future blogs will chronicle the foundational work of key players in Snowy Owl research from other key states, some of whom are among SNOWstorm’s most active partners.

Hopefully our work will continue to inspire awe, wonder, and interest in conservation in everyone who is following what we’re doing. Perhaps Fran said it best in Birding With a Purpose:

“Just one Snowy Owl, seen once, can leave an indelible memory.”

==========================

Hamerstrom, F. 1984. Birding with a Purpose. Iowa State University Press.

Hamerstrom, F. and F. Hamerstrom, 1960. Operation Snowy Owl. Passenger Pigeon 22:126-128.

Hussong, C. 1960. Operation Snowy Owl in Green Bay. Passenger Pigeon 22:129.

Sindelar, C. 1966. A comparison of five consecutive Snowy Owl invasions in Wisconsin. Passenger Pigeon 28:103-108.